After four years of fashion design study and 10 years working in the garment industry my relationship with textiles has gone thorough swings and roundabouts. I was never a serial shopper (I did enough of that in my day jobs), but I was a mass producer; feeding a market with seasonal ranges of clothing; many of which were disposable. This year, after much consideration, I made a leap into a new venture concentrating solely on communicating environmental issues and promoting sustainable practices. While I still very much appreciate design and creativity, after a decade in the garment industry I realised how separate the world of fast fashion was to sustainability.

This article centres around the idea that fast fashion demands clothing that is Cheap, Fast and Good, and by that I mean products that are affordable in selling price, fast reacting to trends and market demands and good in terms of function and quality. The industry, whilst creative in many senses, can be hugely demanding to meet market expectations and utterly fickle considering the longevity of fast fashion clothing. As a developer the expectations from my markets were to have clothing that was Good, Fast and Cheap. Of course, realistically that’s impossible and I would always push back on these expectations and present a challenge to pick only two. Because you can’t have all three, which do you want?

The Textile Industry

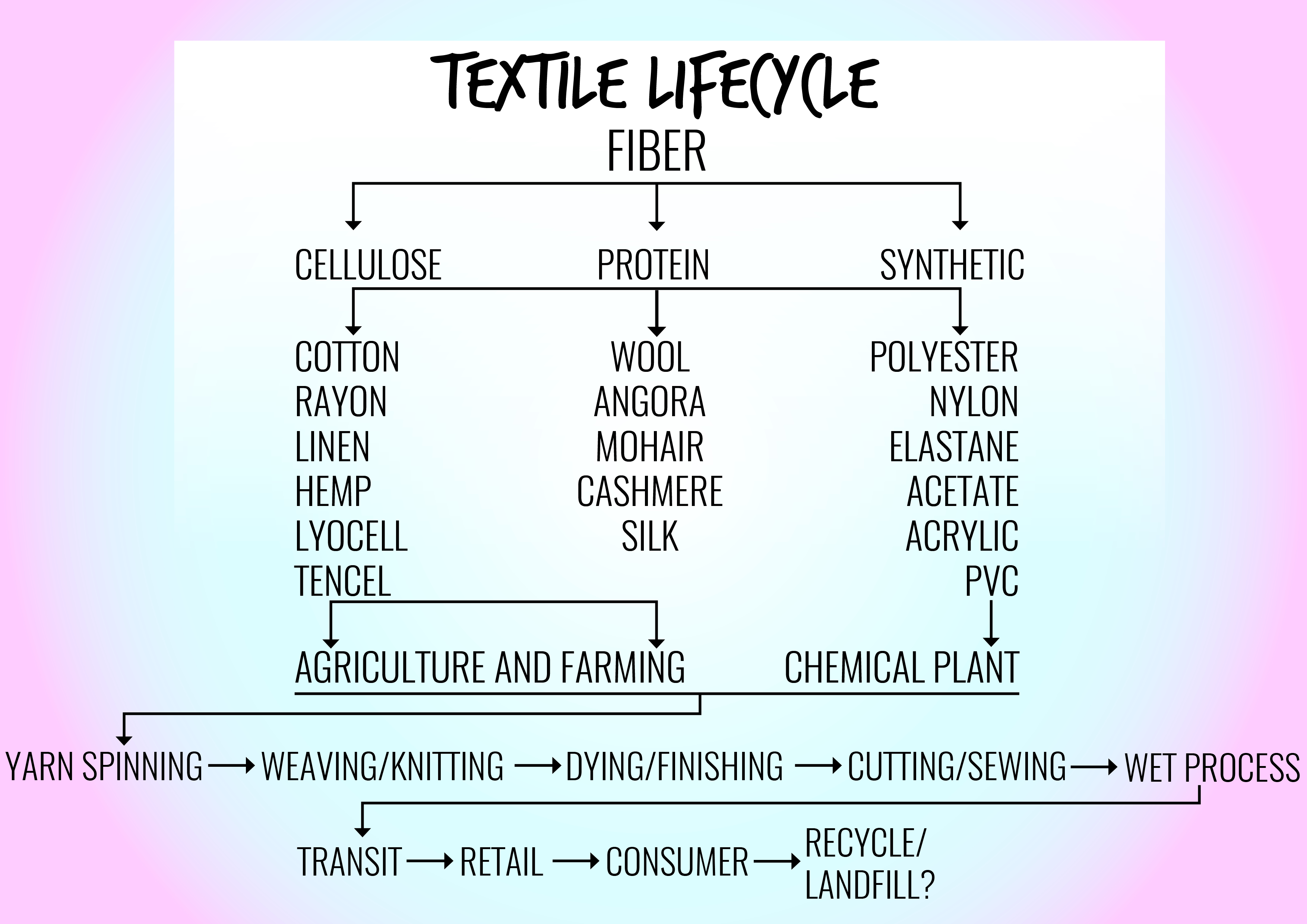

In order to understand how textiles and clothing are produced we need to go back to basics and look at how the fibres are produced. Fibres for textiles fall under three categories: cellulose (plant based), protein (animal based) and synthetics (chemically produced). Both cellulose and animal derived fibres are produced through agricultural processes, which often involve intense farming and irrigation. I have singled out two types of fibres for analysis and I will discuss the economic effect of cotton farming on developing economies and the environmental effects of synthetic fabric production and wear.

Understanding the economic effects of textile production on developing economies

The cotton industry is one of the most arduous means of crop production and it reaps very little income for the small-scale grower. Farmers’ suicides are a grim reality within a cotton growing industry riddled with corruption and with a rate of 270,000 Indian cotton farmer suicides since 1995 it’s easy to correlate the epidemic with the arrival of agrochemical companies such as Monsanto, Cargill and Syngenta to the Indian market. Agrochemical multinational companies supply a patented GM seed for 95% of cotton crops in India. The patented seeds are genetically engineered with a variety of genes and proteins designed to fight off common crop pests and yield a thriving crop. This might seem ideal for a struggling farmer, however the crops often become immune to pests such as the Pink Bollworm and require greater quantities of fertilisers and insecticides which are toxic for the labourers who dispense them in the fields. Traditional farming in India, as well as in many agricultural nations, have historically farmed crops with either open-air pollinated seeds or heirloom seeds. The GM seeds now saturated in the Indian market are hybridised seeds which, by human intervention control pollination. Any biodiversity which was once plentiful will cease in a monoculture landscape, making it impossible for local subsistence farmers to grow food. For the cotton grower the first yield of GM hybridised plants grow strong and plentiful due to a phenomenon called ‘hybrid vigor’. When, however, the idle plant goes to seed, those seeds are genetically unstable and cannot be saved and re-grown the following year. Every farmer using GM hybridised seeds must re-order those same seeds at increasing costs every year. Cotton by weight, earns the farmer a very low wage trapping them into a cycle of poverty which is extremely difficult to escape. It is very common for farming families to fall into debt with the multinational seed companies and their distributors, the end result is often losing their land in order to pay off the debt. For further reading on cotton growing and denim production you can read back on the archived article Closing the Loop on Denims Lifecycle.

Understanding synthetic textile production and its impacts on the environment

If the above insights into cotton farming wasn’t depressing enough I’ll now move onto synthetically made fibres (I am skipping delving into the world of animal fibre farming but you can read up on this from animal activist group Peta, be warned it’s not for the feint hearted!). For the purpose of narrowing this topic, I will focus on the chemicals used in textile production and their potential effects on the environment. Textile manufactures can use over 8000 chemicals in the various processes involved in fabric production, including polyethylene terephthalate which is used in the process of making polyester. Wastewater effluents from poorly managed factories can contain high amounts of chemical agents such as colour fixing resins or anti-crease treatments, many of which can contain formaldehydes, which can be damaging to human health and biodiversity. Heavy metals such as chromium, arsenic, copper and zinc, which are widely used for achieving colour pigments in textile dyes, can also leach from the factories through water effluents. The contaminated water can block the penetration of sunlight from the surface of the water preventing photosynthesis, which will compromise the heath of everything living within and around the river.

Many chemicals are now being identified as potentially hazardous to human health and the environment. Many countries have acted swiftly banning the use of such chemicals within their own industries or banning the import of products containing them. One such chemical, which is gaining much momentum as being potentially hazardous is PFCs (perfluorinated chemicals). The use of PFCs in textiles started in the 1950s but are only now recognised as being harmful to natural life. These compounds enter the environment when manufactured, used and discarded. PFCs are commonly found in materials which are stain or water resistant such as a rain-jacket, a tent and more disturbingly food packaging. They are also found in flame retardants and non-stick frying pans. Many outdoor apparel brands are working towards eliminating PFCs from their products, however chemical regulation in governing States is paramount to prevent their use in everyday materials. The chemical is persistent and has been found in human tissues both in industrial regions and remote parts of the globe. Greenpeace conducted a study in 2016 examining a range of outdoor gear for hazardous PFCs in 40 popular outerwear products. Their test revealed that only four of the tested products were free of PFCs. You can read the report ‘Leaving Traces – The hidden hazardous chemicals in outdoor gear’ here.

Fast Fashion- Consumer Behaviours

Growing up in Ireland in the 80’s and 90’s I didn’t have access to the high-street market like we see today in many European Cities. Much has changed, between the arrival of new fast fashion stores and the globalisation of online retail shopping. So why has clothing shifted to become a disposable product and what is the future of our throw-away society?

The turn of the 20th century saw new innovations in chemical technology which led to exponential developments in new forms of plastics including synthetic fabrics. In 1939 the chemical company DuPont introduced the Nylon stocking to the market, replacing the costly silk stocking. The demand for the cheap stockings was so high that when WWII hindered the production of the stockings Nylon Riots broke out and sent Americans into hosiery hysteria! Since the breakthrough of synthetic textiles, producers could meet market demands for affordable clothing, turning out fast fashion that mimicked catwalk styles. Fighting over stockings might seem amusing now, but let’s not forget the Black Friday death count and related injuries totting up to 121 incidents to date (It’s no joke and you can track this morbid rate on blackfridaydeathcount.com).

Over the last 70 years the mass production of fast fashion clothing has escalated as a result of our emerging throw-away culture. Wardrobes can only fit so many clothes, so as a result textiles are being discarded, dumped, recycled or donated in order to make space for a new batch of trends. This throw-away behaviour doesn’t stop at wearable fashion but trickles down into other textile commodities such as single use camping tents and soft homeware furnishings (I’ll share some of my experiences with these behaviours in a later follow-up post). Depending on its quality and style the garment may become redundant to its wearer after a few washes or when the fashion trend has run its course. Consumers and fashion lovers will soon want the next big trend; they may want a fresh new look for a holiday, or for a new job or for the start of school term. They can either throw the old clothing out with the household waste, or they can donate or recycle the garment. Earlier this year luxury brands such as Burberry made headlines when they revealed they had burned tens of millions of dollars of unsold goods in order to preserve the exclusivity of the brand which never reduces its prices to shift old stock. Their annual report in July revealed that 28.6 million pounds, or about $37 million, of clothing and cosmetics were burned. The behind the scenes activity of standard garment production and brand ideology is hair raising.

In the USA 11,793,400 tons of textiles are discarded annually. To weigh that up visually, that is about the weight of two times the Great Pyramid of Giza. Only 15% of this clothing waste is collected by charities. The economic loss of goods that are not recycled equates to $88 billion annually (includes the physical material wasted and the resources invested into its production). Many second hand charity shops are overwhelmed with clothing donations and I have rarely found a clothing bank which isn’t busting at the seams. The sight of the metal container over-flowing with clothing and rags is a sober reminder that the world doesn’t need more clothes.

The economic impact that foreign discarded/donated clothing has on local textile industries in developing countries can be devastating but it can also create emerging and perhaps controversial shifts in culture. Not only does cheap used clothing threaten to wipe out local enterprise it has also stamped out culture and traditional dress. It’s not uncommon to see last seasons’ catwalk inspirations mixed in with traditional regional style in rural African regions. However with the expanse of online selling and globalisation, the cross-culture of modern clothing teamed with traditional weaves and cuts has also created thriving enterprises for bright young designers and thinkers. Street-style clothing in Kenya is a relativity new phenomenon, as a movement it can often be frowned upon by those who want to uphold cultural tradition, however Gikomba Market in Nairobi is a melting pot of creativity where used thrift clothing meets traditional textiles creating a unique look for the style conscious wearer. Check out the styles on @thriftsocialnairobi.

Cheap – the value of clothing

The fashion retail giants such as H&M, Primark, Tesco, Zara and Uniqlo can react quickly to fashion trends and deliver weekly collections at astonishingly low prices. The attainability of fashionable clothing at rock bottom prices has encouraged a mindset across much of society that it’s okay to buy bundles of clothing for various occasions and discard them after a few wears. According to a report conducted by research firm Sanford C. Bernstein, the average selling prices of women’s clothes in H&M and Primark is £10.69 ($16.37) and £3.87 ($5.06), respectively. How can a clothing item that undergoes so much agriculture, processing, development and energy costs profit at an average selling price of under £4. In order to deliver cheap clothes quickly, clothing brands develop collections in some of the poorest regions in the world where political instability and poverty outweigh environmental concerns. Overloaded factories can often outsource production to smaller un-audited factories and this is often where policies and safety regulations lapse. There is unimaginable pressure and expectations for garment factories to produce good quality clothing, cheaply and quickly. Even some of the larger established factories will cut a corner so as not to lose a big order from a client. Does the date April 24, 2013 ring a bell with you? I’ll admit, I had to look it up, but on this date the Rana Plaza disaster saw 1,138 innocent garment workers lose their life when the Savar building in the Dhaka district of Bangladesh collapsed. You might think the world would have spotlighted the injustices in garment production in poor developing nations, but this did not happened, most people still want cheap clothing and they don’t always want to know who made their clothes. If you do want to write to your favourite brands about their garment production policies you can download this Fashion Revolution Who Made My Clothes Postcard.

Good – The quality of fast fashion clothing

Good quality fabric is not synonymous with fast fashion and we are more likely to find quality in vintage clothing or in slow fashion apparel. Apart from the usual problems we find in cheap clothes such as shrinking, pilling, skewing and weak tensile strength there is a more serious problem which has remained largely invisible until more recent years. Micro-fibres from low quality textiles has become a hot topic of pollution in our waterways. All garments release micro-fibres during washing and wear, but this is especially true of synthetic fabrics which have undergone a lot of processing such as brushing and distressing. Have you ever pulled a new fleece sweater over your head to find your under clothes flecked with billions of lint fibres? Those are micro-fibres and they are potentially disastrous when released into the environment. It seems unavoidable but you can reduce the level of fibres being released by a) buying less synthetic clothes, b) washing your clothes less often, c) invest in a machine with an eco-filter or purchase a simple lint catching bag such as Guppy Friend. Knitted fleece with a soft brushed surface (like a peach) is the top source of micro-fibre loss to the environment. It passes through drains, washing machines, water treatment plants and is released into the sea. At >1mm in size they are an invisible contaminant and impossible to reclaim from the environment.

So what next, where do we go from here? What can you do to reduce the impact that the clothing industry has on society and our environment? It may seem dismal but there are always sustainable solutions even if it seems like the overall effect will be minimal. I am a firm believer that every sustainable action collectively contributes to a better world to live in. I’ve discussed a few ideas in the post already and I’ll summarise some positive actions you can take.

- Avoid fast fashion, invest in quality and know the difference between cheap fabrics and long lasting fabrics.

- Start a capsule wardrobe, rotate with the seasons and cherish your favourite staple items (theres no shame in wearing your jeans until they’re thread-bare!)

- Choose un-treated raw fabrics over processed fabrics. Eg. Raw un-washed denim or non-brushed looped back fleece.

- Mend and up-cycle your clothing.

- Think before you donate, why is the clothing redundant? Divest in such clothing in future.

- Campaign much? #WhoMadeMyClothes?

- Clothing which is torn and worn can be recycled! Bag it up and mark it textile waste, most charities will take the PCW (Post consumer waste) to sell on for making new products.

- Swap clothes around with friends and family- find a local start up, I just discovered Swapsies.

- Wash less- If it’s just a small stain you can spot clean an area or if it just needs some freshening up you can air clothes out.

- Avoid ‘Greenwashing’ and know industry standard terms:

- RDS (Responsible Down Standard)

- RWS (Responsible Wool Standard)

- Organic Cotton (It will use the same amount of water to grow but will reduce the impact on the biodiversity of the land where it’s grown compared to GM cotton)

- BCI (Better cotton initiative: an ethical standard agreement for cotton growers- Mills can purchase a mix of cottons from different sources, even if some bails are BCI and other deliveries are not they can blend the batches and still use the BCI branding)

- Water less (Reduced water usage in the fabric process such as denim and fleece: Oyzone chemical washing can be a replacement for the wet process)

- PCW recycled (Post consumer waste- garments are rarely made of 100% of recycled materials, for tensile strength its usually a blend of virgin materials and recycled)

- Natural dyes (Non chemical dyes without chemical fixers, they will fade naturally with wear but can often age beautifully!)

- Fair trade (Fair wages for produce)

Follow up post coming soon on throw away society!

Rebecca.

Thanks, lots of useful information and detail here.

LikeLike